Trail house

Almere (NL) - 2009

Anne Holtrop

newroom

Ein Essay von Ole Bouman, Direktor des Niederländischen Architekturinstituts NAI in Rotterdam. Wenn alles glatt läuft, sind dies bloß langweilige, leere Platitüden: 1. Menschen brauchen genügend zu essen und zu trinken: gewiss. 2. Sie wollen gesund sein: ganz klar. 3. Ohne Energie können wir nicht leben: logisch. 4. Menschen brauchen ausreichend Platz: ohne Zweifel. 5. Sie brauchen auch Zeit, um sich zu verwirklichen: unbestreitbar. 6. Wenn mehrere Menschen zusammen leben, ist es wichtig, dass sie miteinander gut auskommen: selbstredend. 7. Und wenn Menschen miteinander Handel treiben wollen, um Vorteile aus all diesen Bedingungen zu ziehen, dann muss sich das auch rechnen: natürlich.

Leider ist nichts davon heutzutage selbstverständlich. Wir leben nun einmal in keiner Ära des Friedens; vielmehr folgt eine Katastrophe auf die andere. 1. Die Nahrungsketten sind untergraben. 2. Die Volksgesundheit ist gefährdet. 3. Die Energieressourcen nehmen ab. 4. Vielerorts mangelt es an Raum. 5. Wertvolle Lebenszeit zerrinnt uns zwischen den Fingern. 6. Der soziale Zusammenhalt schwindet. 7. Schließlich wird uns immer deutlicher klar, dass wir viel zu lange Gewinne privatisiert und Verluste der Gesellschaft aufgebürdet haben, was eine tiefe Krise des Wirtschaftssystems zufolge hatte. Heute ist es schon fast ein Klischee, über die Bedrohung der wichtigsten Überlebensstrukturen des Planeten zu sprechen. Es fehlt nicht mehr viel, und auch die Katastrophe wird zur langweiligen Platitüde, die uns selbstverständlich erscheint.

In dieser angespannten Zeit der ungezählten Notlagen stellen wir nun ein Buch über Architektur vor. Dies mag wie ein frivoler Zeitvertreib daherkommen, eine bloße Pause, in der uns die Pracht und beruhigende Wirkung eines schönen Gebäudes über eine immer bedrohlichere Epoche hinwegtrösten soll. Aber unser Beruf hat keine Zeit für Entspannung, da rückblickend klar ist, dass die Architektur sehr stark zur Ausbreitung weltweiter Krisen beigetragen hat. Soll die Architektur also ihren Mehrwert unter Beweis stellen und die Last ihrer Schuld abschütteln, bedarf sie besserer Argumente als der bloßen Fähigkeit, Unterschlupf vor den Elementen zu bieten.

Bei genauerer Betrachtung stellt sich diese Last als gewaltig heraus. Krisenbilder im Kopf sind stets auch Bilder von Architektur: verstopfte Straßen, überfüllte Flughäfen, automatisierte Warenumschlagplätze, Massenhaltungen von Kühen, Schweinen und Hühnern, Fleischfabriken, Fast-Food-Lokale, Einkaufszentren, Hypermärkte und Quarantänezonen, weltweite Werkstofftransporte, Zersiedelung, Schlafstädte in der Wüste von Arizona, Sperrgebiete und Sicherheitsmauern, verlassene Häuser in Geisterstädten wie Detroit oder Seseña Nuevo. All dies begann mit Entwürfen.

Doch das Argument funktioniert in beide Richtungen: Hätten diese Bilder der Krise nicht bis vor kurzem noch als Beispiele des unerhörten Erfolgs der Globalisierung gelten können? Denken wir etwa an einen international gefeierten Architekten, der ständig durch die Welt jettet und so viele einzigartige Gebäude wie möglich entwirft, die ihrerseits einen bewundernden Massentourismus auslösen helfen: Sind das denn nicht die einmaligen, fantastischen Architekturgebilde, die von weither kommen und die jeweilige Stadt bekannt machen sollen? War es nicht eben diese Praxis, die den unerhörten Ruhm mancher Architekten begründete? Wie kann dieses bejubelte Podest über Nacht zum Symbol kulturellen Bankrotts werden?

Der Grund dafür ist nur im gleichermaßen schnellen Begreifen der Krise zu finden. Architektur, Design und Bauwesen werden immer stärker als Teil des Problems betrachtet. Art und Weise der Selbstorganisation und Selbstpräsentation der Branche gelten heute zunehmend als Soziallast: Gebäude, die an Zugänglichkeit und Erreichbarkeit, einem Beitrag zur Gesellschaft und praktischer Benutzbarkeit ebenso desinteressiert sind wie an der Idee, den Konsum fossiler Brennstoffe zu senken bzw. sich über den Ursprung der Baustoffe, die Effizienz des Bauvorgangs oder zukünftige Erhaltung Gedanken zu machen. Manche wollen schon das Schreckgespenst eines völlig verantwortungslosen Berufsstands ausgemacht haben, der es darauf anlegt, ohne Rücksicht auf Verluste oder Marktbedingungen immer höhere Honorare einzufordern. Ein Berufsstand, der das Bemühen um Achtung vor seiner Kulturleistung auf bloßes Spektakel gründet, lebt gefährlich.

Doch die Lösung liegt nicht in der Abschaffung der Architektur. Der sündige Architekt kann nur durch den erlösenden Architekten gerettet werden – und zwar in der Person von Architekturschaffenden, die sich der Herausforderung stellen.

Deshalb befasst sich dieses Buch vor allem mit niederländischer Architektur. Die Niederlande sind in mancher Weise überdurchschnittlich hart von der gegenwärtigen Krise betroffen und müssen sich mehr als andere Länder um eine Lösung bemühen. Wenn das Land diese Herausforderung ignoriert, verliert es seine Existenzberechtigung. Ohne Innovation sind die Niederlande als unabhängiges Land dem Untergang geweiht. Die Fakten sprechen hier eine klare Sprache. Die hohe Bevölkerungsdichte hat die Niederlande gezwungen, eine führende Rolle in der Industrialisierung der Nahrungsproduktion einzunehmen. Der immer größere Anteil älterer Menschen stellt das Gesundheitswesen vor schwere Herausforderungen. Ohne ständige Energiezufuhr wird das Land überflutet. Es benötigt mehr Boden, um den demografischen Druck abzufedern und sich ändernde Familienstrukturen einzubeziehen. Es benötigt Zeit, um den Wert von Innovationen zu testen. Es benötigt sozialen Frieden, um die vielen Ziele auch umzusetzen. Und als Hort des Kapitalismus ist es an neuen Maßstäben für das Weltwirtschaftssystem beteiligt und hat vielleicht mehr als andere Staaten dabei zu gewinnen. Fällt den Niederlanden angesichts dieser Herausforderungen nichts Neues ein, wird das Neue seinerseits mit voller Macht über die Niederlande herfallen.

Es stellt sich hier die Frage, ob die niederländische Architektur einer solchen Aufgabe gewachsen ist. Die Antwort steht keineswegs fest. Schließlich ist der Druck des Einfach-Weiterwurstelns beträchtlich. Zum Beispiel wird in Fachkreisen noch immer viel Energie auf alte Grabenkämpfe wie dem zwischen Modernisten und Traditionalisten aufgewendet – eine auf der Überzeugung beruhende Kontroverse, dass es in der Architektur dem Wesen nach um Stil und äußere Form gehe und Architekturschaffende sich daher für die Schule entscheiden, der sie jeweils angehören wollen: jener der modernen Ära oder jener, die dem Kunden „das gibt, was er will“. Dieser angebliche Kampf um Leben und Tod zieht sich nunmehr schon fast ein Jahrhundert hin.

Eine neuere Ansicht ist, dass ein Gebäude nur dann als Architektur gelten kann, wenn es ein intelligentes Konzept, beruhend auf einer umfangreichen Analyse von Kontext, Programm und zeitgenössischer Architektur- und Philosophiedebatte, verkörpert. Wurde die niederländische Architektur nicht weltberühmt mit SuperDutch, dem Werk einer Generation, die sich durch eine noch nie dagewesene konzeptuelle Kraft auszeichnete? Dieser Ansatz machte eine Gruppe äußerst intelligenter EntwurfskünstlerInnen zweifellos berühmt, ist aber wohl kaum Grund genug, um fortan in architektonischer Hinsicht einfach so weiterzumachen.

Heute, da sich das Jahr 2009 dem Ende nähert, sind Zweifel angebracht, ob der Berufsstand in den Niederlanden widerstandsfähig genug ist, das Steuer herumzureißen und neue Chancen zu ergreifen. Nach einer jüngeren Studie des Königlichen Instituts Niederländischer Architekten (BNA) fiel ein Drittel der Architekturbüros in weniger als zehn Monaten der Krise zum Opfer, und der Reichsbaumeister kündigte ein Nothilfsprogramm an, um das Entstehen einer infolge der Konjunkturprobleme und drastischen Einschnitte im Bauwesen „verlorenen“ Generation zu verhindern.

Die Architekturbeispiele in diesem Buch haben mit typisch niederländischer Architektur in diesem Sinne oder auch mit einem Hilfsprogramm kaum oder gar nichts zu tun. Sie sollen vielmehr ein radikaler Teil der Lösung sein. Diese Architektur bietet Lösungen für Fragen an, die sowohl viel größer als die Architektur per se als auch ohne Architektur unlösbar sind. Bei dieser Architektur geht es nicht um die angestrebte Form oder die mögliche Analyse, sondern vor allem um das, was nötig ist, um die Fähigkeit der Architektur, drängende Probleme zu lösen. Diese Architektur lässt sich nicht von der derzeitigen Marktsituation ablenken, in der sich die Frage stellt, ob es überhaupt Arbeit für Architekturschaffende geben wird. Vielmehr geht es um eine Vision der Zukunft und um die Konzentration, die man braucht, um dieses Bild scharf im Auge zu behalten. Damit geht es auch um die spekulative Denkweise junger und älterer Architekturschaffender, die für eine solche Vision grundlegend ist, und um die Recherchen hinter ihren Entwürfen.

Dieses Buch beginnt und endet jenseits der Architektur und stellt eine einzigartige Möglichkeit für die zeitgenössische Architektur dar – nämlich die Wiederentdeckung einer sozialen Notwendigkeit, die konsequent qualitätvolle Architektur erschafft. Solche Augenblicke sind eine historische Rarität; sie ereignen sich nur dann, wenn die alten Methoden nicht mehr angebracht und neue Methoden noch nicht auszumachen sind. Diese Krise ist eine zu wertvolle Chance, um sie zu versäumen. Sie bietet die Gelegenheit, zum Ursprung der Architektur als kreative Raumorganisation des menschlichen Lebens zurückzukehren – nicht durch die Wahl eines bestimmten Stils oder konzeptuelle Analysen, sondern durch die Erfindung neuer räumlicher Konstellationen; nicht durch Raumzuteilung und Umsetzung eines bestimmten Programms, sondern durch Mitschaffung einer Raumorganisation für eine Vielzahl von Programmen; nicht durch den Bau von Dingen im Raum, sondern durch die Organisation von Abläufen in der Zeit; kurz, eine Rückkehr nicht zum physischen Objekt, sondern zur erbrachten Leistung. Bei dieser Architektur geht es nicht um oberflächliche Schönheit, sondern um Ergebnisse. Endlich erweist sich die Architektur als unvergleichliches Innovationsfeld.

Diese Erkenntnis mag den Leser oder die Leserin überraschen. Ein Überblick über moderne Innovationstheorien zeigt bald, dass Erwartungen in Bezug auf zukünftige soziale Neuerungen und damit zukünftigen ökonomischen Wohlstand vor allem auf die Hochtechnologie abstellen: Informationstechnologie, Biotechnologie, Nanotechnologie und Neurotechnologie – in anderen Worten: Bits, Gene, Atome und Neuronen. Hier konzentrieren sich gigantische Ressourcen in der Forschung, hier sind soziale Relevanz und soziale Achtung verortet. Niemand in der weltweiten Wissensgesellschaft setzt mehr auf die Architektur, einen Berufsstand, der mit Stein, Boden, Raum, Langsamkeit assoziiert wird. Noch weniger ist zu erwarten, dass sich radikale Neuerungen in den genannten Technologiebereichen direkt in der Architektur widerspiegeln werden, ganz im Gegensatz zu den Ergebnissen früherer technischer Revolutionen: Kirche, Palast, Fabrik, Bahnhof, Bankgebäude. Wie kann die Architektur heute Vorteile aus den Fortschritten der Genetik und Nanotechnologie ziehen? Die Bedrohung der Architektur entspringt nicht nur der Wirtschaftskrise, sondern auch einer Krise der Motivation. Dauert diese zu lange an, könnte noch eine Talentkrise dazukommen.

Was kann die Architektur tun, um dieses Szenario abzuwenden und ihre soziale Rolle in der Gegenwart mit ihrer zukünftigen Mission in Einklang zu bringen? Ganz einfach – sie muss mit dem Notwendigen anfangen. Mehr als irgendeine neue Technologie liefert die alte Technologie der Architektur Lösungen für Probleme im Zusammenhang mit Nahrungsketten, Gesundheit, Energieflüssen, Raumknappheit, Zeitmanagement, sozialen Spannungen und dem heutigen Wirtschaftssystem.

Benötigt wird eine Raumorganisation, die den Menschen wieder zu Eigenständigkeit verhilft, die gesündere Milieus schafft, die Energie produziert, anstatt sie bloß zu verbrauchen, die Raum und Zeit nicht auffrisst, sondern sie vielmehr erzeugt, die den Zusammenhalt fördert – eine Raumorganisation, deren Wert als einheitlicher Prozess von Entwurf, Gebäude und Erhaltung definiert ist. Dies ist eine ebenso anspruchsvolle Aufgabe wie eine Apollo-Raumstation; in der niederländischen Dimension ist sie mit der symbolischen Kraft der Deltawerke vergleichbar. Der Architektur bietet sich heute eine Chance, die nur selten wiederkehrt.

Eine Architektur, die sich auf die vielen Möglichkeiten der Intensivierung und Kombination konzentriert, ist ein realistischer Ansatz. Im Gegensatz zu einer Architektur der monoprogrammatischen Zonen, rigiden Zweckbindung von Räumen, Flächenwidmungspläne und hoch individuellen, nicht wiederholbaren Statements finden wir eine Architektur, die aus dem Teilen von Raum, Dienstleistungen, Energie, Verkehrsmitteln, Öffentlichkeit und Werten Nachhaltigkeit gewinnt – eine Architektur, die durch das Teilen ganz neue Typologien schafft.

Dieses Buch bietet zahlreiche Beispiele einer solchen Architektur: von CO2-neutralen zu Energie erzeugenden Gebäuden und Landschaften, von qualitativ hochwertiger Architektur für einkommensschwache Gruppen zu einer Villa aus Abfallstoffen, von temporären Hotels in Abrisszonen zur Umgestaltung bestehender Sozialwohnungen, von einzigartigen Unternehmensbündnissen auf regionaler Ebene zu kooperativen und produktiven Teams, die die lokale Bevölkerung einbinden.

Architektur bietet eine solche Vision für die Zukunft schon heute an, wie dieses Buch belegt. Die hier vorgestellten Architekturschaffenden mögen im Alltag oft Konkurrenten sein – hier zeigen sie jedoch eine erstaunliche Einstimmigkeit in ihren Ambitionen für den Berufsstand. Dies ist kein Pakt, keine Bewegung, bei der alle in dieselbe Richtung blicken müssen, sondern eher ein Wettbewerb, bei dem die Teilnehmer von denselben innovativen Motivationen angetrieben werden: Ein Berufsstand macht sich auf, die Probleme zu lösen, die er mitgeschaffen hat.

Visionen der Zukunft, Bilder, die ihnen Macht verleihen, zielgerichtete Strategien, die Kraft der Überzeugung, um diesen Strategien zu folgen – all dies findet sich in diesem Buch. Was fehlt, ist die effiziente Umsetzung durch Entscheidungsträger. Wir hoffen, dass dieses Buch ihnen helfen wird, eben jene Entscheidungen zu treffen.

(Ole Bouman, Einleitender Essay zum Katalog der Ausstellung „Architecture of Consequence“, 2009, übersetzt von Sigrid Szabó)

Almere (NL) - 2009

Anne Holtrop

newroom

Heemskerk (NL) - 2010

Anne Holtrop

newroom

Tilburg (NL) - 2010

NEXT ARCHITECTS

newroom

Almere (NL) - 2008

NEXT ARCHITECTS

newroom

Amsterdam (NL) - 2007

NEXT ARCHITECTS

newroom

Leiden (NL) - 2009

pasel.kuenzel architects

newroom

Leiden (NL) - 2010

pasel.kuenzel architects

newroom

Leiden (NL) - 2009

pasel.kuenzel architects

newroom

Leiden (NL) - 2011

pasel.kuenzel architects

newroom

Amsterdam (NL) - 2006

VenhoevenCS

newroom

Utrecht (NL) - 2009

VenhoevenCS

newroom

Amsterdam (NL) - 2006

VenhoevenCS

newroom

Zwolle (NL) - 2009

Atelier Kempe Thill

newroom

Rotterdam (NL) - 2009

Atelier Kempe Thill

newroom

Amsterdam (NL) - 2011

Atelier Kempe Thill

newroom

Hoogvliet (NL) - 2011

van Bergen Kolpa Architecten

newroom

Amphibious Housing in the Netherlands outlines the trends and experiments in the realm of architecture on and in close proximity to water. It is impossible to imagine our spatial and urban planning without water, and this book reveals what is happening in the realm of amphibious housing and how that

Autor: Anne Loes Nillesen, Jeroen Singelenberg

Verlag: NAI Publishers

For almost 25 years, Architecture in the Netherlands has provided an indispensable overview of recent projects for everyone who is interested in or professionally involved with Dutch architecture. The editorial team presents and comments on 30 projects selected from the 400 or more submissions of work

Verlag: NAI Publishers

Today, architects around the world are resetting the tools of design and creating a language that includes variation and complexity. In this book, theory, history and research are integrated with digital design techniques and computer-based fabrication technologies to give us a first peek into what the

Hrsg: Lars Spuybroek

Verlag: NAI Publishers

Nonstandard architecture is bespoke architecture. The buildings of today are designed with digital tools and produced by digitally controlled processes. This opens up a revolutionary new perspective on the nature and realization of design and calls for a whole new debate about what is beautiful in architecture.

Autor: Kas Oosterhuis

Verlag: NAI Publishers

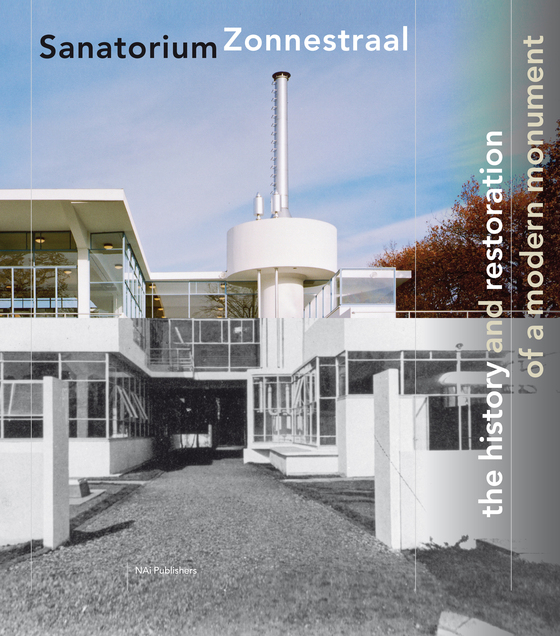

Ever since its completion in 1928, Jan Duiker's Sanatorium „Zonnestraal“ in Hilversum has probably been the most canonical and internationally celebrated example of Modern Movement architecture in The Netherlands. After an extensive restoration of more than thirty years, the project is completed. The

Hrsg: Paul Meurs, Marie-Thérèse van Thoor

Verlag: NAI Publishers

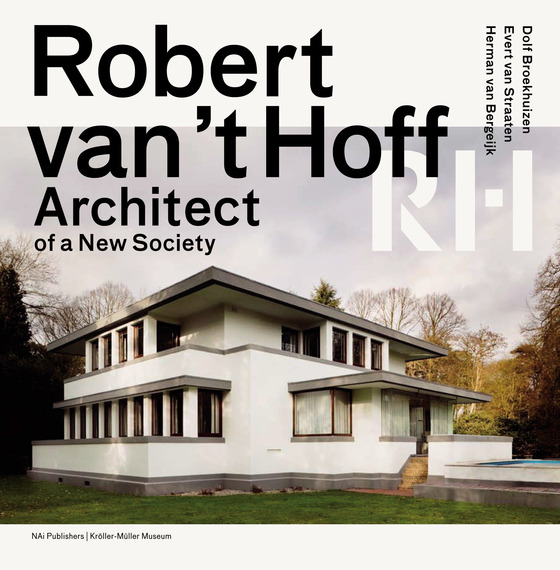

Dutch architect Robert van ’t Hoff (1887-1979) created innovative designs for houses at the beginning of the twentieth century; Verloop Summer House and Villa Henny are the most striking. Villa Henny brought him international fame. This beautiful „concrete villa“, realized around 1918, has become an

Hrsg: Dolf Broekhuizen

Autor: Evert van Straaten, Herman van Bergeijk

Verlag: NAI Publishers

For the past 33 years, Bureau B+B has been a trendsetting agency and a laboratory for landscape architecture. NAi Publishers presents Bureau B+B Urbanism and Landscape Design: A Collective Genius, 1977-2010, a high-spirited survey of the projects of this interdisciplinary agency.

Since it was established

Verlag: NAI Publishers

Health care architecture in the Netherlands describes the evolution of buildings for health care: hospitals and psychiatric institutions as well as housing and care facilities for the elderly. Architecture is particularly significant in health care it reflects developments in care, medical innovations,

Autor: Noor Mens, Cor Wagenaar

Verlag: NAI Publishers

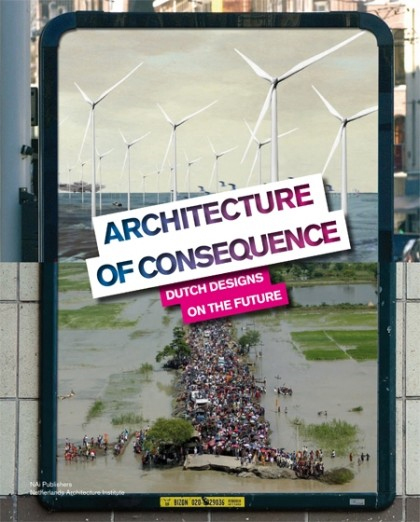

Sustainable food production, alternative sources of energy, the need for social cohesion in a healthy environment – these are a few of the essential issues of our time that rub shoulders in environmental planning and architectural design. That forms a tremendous potential for social renewal.

In this

Hrsg: Ole Bouman

Verlag: NAI Publishers

Der holländische Fotograf Bas Princen (*1975) gehört zu einer Generation von Fotografen, die auf ganz ungewöhnliche Weise Bezug zu den sogenannten »New Tophographics« nehmen. Diese Gruppierung von zehn mittlerweile großen Namen der Landschaftsfotografie, zu denen Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Stephen Shore

Hrsg: Moritz Küng, deSingel, international arts centre, Antwerp

Verlag: Hatje Cantz Verlag

Prompted by the international success of the first hardback edition, this monograph about one of the seminal figures of the Modern Movement, the Austrian philosopher, sociologist and urban planner Otto Neurath (1882-1945), is now being released in paperback. His ground-breaking ideas about the modern

Autor: Nader Vossoughian

Verlag: NAI Publishers

Mobile phones, public transport smart cards, security cameras and GPS systems in our car - we are surrounded by digital devices. They track us, guide us, help us, and control us. The book Check In / Check Out. The Public Space as an Internet of Things shows us how our digital and physical worlds are

Verlag: NAI Publishers

For almost 25 years, Architecture in the Netherlands has provided an indispensable overview of recent projects for everyone who is interested in or professionally involved with Dutch architecture. The editorial team presents and comments on 30 projects selected from the 400 or more submissions of work

Autor: Timo de Rijk, Adele Chong

Verlag: NAI Publishers

For almost 25 years, Architecture in the Netherlands has provided an indispensable overview of recent projects for everyone who is interested in or professionally involved with Dutch architecture. The editorial team presents and comments on 30 projects selected from the 400 or more submissions of work

Verlag: NAI Publishers

Wohnungsbau jenseits des Standards. Noch immer lohnt sich der architektonische Blick über die Grenze. Allein in den letzten sieben Jahren wurden in den Niederlanden über 600 000 Wohnungen fertiggestellt – meist gekennzeichnet von hoher planerischer und gestalterischer Qualität. Wohnumfeld, Großzügigkeit,

Autor: Leonhard Schenk, Rob van Gool

Verlag: DVA

Ein Ausstellungsmagazin der besonderen Art: „West Arch – A New Generation in Architecture“ präsentiert 25 Architekturbüros aus Belgien, Deutschland und den Niederlanden, die vor allem ein experimenteller und unkonventioneller Umgang mit zeitgenössischen Fragestellungen an die Architektur auszeichnet.

Hrsg: Brigitte Franzen, Marc Grünnewig, Florian Heilmeyer, Jan Kampshoff, Andrea Nakath

Verlag: JOVIS

[Zwillingsheft 175: AMO – Projektionen] („http://www.nextroom.at/publication_text.php?publication_id=993&cat_id=2“)

Die Ausgabe beschäftigt sich mit den großen Architekturprojekten der letzten Jahre. Diese haben Alexander D’Hooghe dazu verführt, von einem „monumental turn“ zu sprechen, was sich jedoch

AMO – Projektionen [Zwillingsheft 174: OMA – Projekte] (http://www.nextroom.at/publication_text.php?publication_id=991&cat_id=2)

Für Rem Koolhaas bietet AMO den organisatorischen Rahmen für die Arbeit jenseits konventioneller Architektur. Das Heft setzt sich mit der bereits in dieser projektiven Definition

In den Niederlanden ist das „supermoderne“ Spektakel des vergangenen Jahrzehnts einem Pragmatismus gewichen, der auf marktgerechte Erzeugung von Vielfalt aus ist. Das Programm heißt: Stadtumbau und Verdichtung.

Niederländische Entwürfe für die Zukunft.

Wenn alles glatt läuft, sind dies bloß langweilige, leere Platitüden: 1. Menschen brauchen genügend zu essen und zu trinken: gewiss. 2. Sie wollen gesund sein: ganz klar. 3. Ohne Energie können wir nicht leben: logisch. 4. Menschen brauchen ausreichend Platz: ohne Zweifel. 5. Sie brauchen auch Zeit, um sich zu verwirklichen: unbestreitbar. 6. Wenn mehrere Menschen zusammen leben, ist es wichtig, dass sie miteinander gut auskommen: selbstredend. 7. Und wenn Menschen miteinander Handel treiben wollen, um Vorteile aus all diesen Bedingungen zu ziehen, dann muss sich das auch rechnen: natürlich.

In this fraught period of multiple emergencies we are presenting a book about architecture. This may sound like a flippant diversion, a pause to contemplate the magnificence and reassurance of a beautiful building in an era that is growing more and more menacing. But the profession has no time for such relaxation as it is evident in retrospect that architecture has contributed mightily to a spread of global crises. If architecture is to demonstrate its added value, and to shed its burden of guilt, it needs better arguments than its ability to offer shelter.

Upon closer inspection that burden turns out to be massive. Conjure up images of the crisis and what you see is architecture: jammed roads, packed airports, automated transhipment centres, vast cowsheds, battery farms for pigs and chickens, meat factories, fast food outlets, shopping malls, hypermarkets and quarantine zones, worldwide material transportation, urban sprawl, condominium cities in the desert of Arizona, no-go areas and security walls, abandoned homes in ghost towns like Detroit or Sesena Nuevo. And it all started with design.

But here the argument cuts both ways. Couldn’t these images of the crisis until recently be considered as exemplars of the unprecedented success of globalization? And still. Think of an internationally acclaimed architect who is constantly jetting around the world, designing as many unique buildings as possible that in turn help generate an admiring mass tourism. Isn’t this the one-off architecture that comes from far away to put the city on the world map? Hasn’t this practice brought architects to a pinnacle of unparalleled fame? How can that pinnacle become an overnight symbol of cultural bankruptcy?

The reason for this can only be found in the equally rapid awareness of the crisis. Architecture, design and construction are increasingly seen as part of the problem. The way in which this branch organizes and presents itself is now often taken to be a social debit – buildings that pay no heed to how they can be reached or accessed nor to what they contribute to society, how they can be adapted for use, the reduction of fossil fuel consumption, the provenance of their materials, the efficiency of the building process and their future management. Some people can already see the looming spectre of a totally irresponsible profession that seems bent on pricing itself out of the market, whatever the consequences. A profession that bases its efforts to win cultural respect on mere spectacle is living dangerously.

But the solution cannot dispense with architecture. The architect as sinner can only be redeemed by the architect as saviour, in the person of an architect who faces up to the challenge.

That is why this book is in particular about Dutch architecture. The Netherlands is in some respects harder hit than the average by the present crisis and will have to strive more than most other countries to find a solution. If this country ignores the challenge it will cease to exist. Without innovation the Netherlands is doomed to disappear as an independent country. Just look at the facts. The high population density has forced the Netherlands to become a leader in the industrialization of food production. The growing elderly population is a challenge to health care. Without a permanent supply of energy the country will be flooded. It needs new land to accommodate demographic pressure and to cater for changing lifestyles. It needs time to prove the value of innovations. It needs social peace to pursue its many desires. And as a crucible of capitalism, it is involved in and stands to gain more than any other country from a new benchmarking of the global economic system. If the Netherlands, under all this pressure, fails to think up something new, what is new will come up with something for the Netherlands.

The question now is whether Dutch architecture is up to the task. That is by no means a foregone conclusion. After all, the pressure just to keep plodding on is enormous. For example, a lot of energy in professional circles is still wasted on old feuds such as that between the modernists and the traditionalists, a controversy rooted in the notion that the essence of architecture is about style, external form, and that the architect therefore opts for the school to which he or she wants to belong, that of the modern era or that of providing „what the customer wants“. This supposedly life-and-death struggle has been dragging on for most of a century by now.

A more recent notion is that a building can only be architecture if it is the embodiment of an intelligent concept, based on an extensive analysis of context, programme and the current architectural and philosophical debate. Didn’t Dutch architecture become world famous with SuperDutch, the work of a generation that profiled itself with an unprecedented conceptual strength? This approach has certainly made a group of extremely intelligent designers famous, but it is debatable whether this is reason enough for architecture in general to continue along the same lines in future.

Now, past mid-2009, it is doubtful whether the architectural profession in the Netherlands has enough resilience to turn the tide and seize new opportunities. According to a recent investigation by the Royal Institute of Dutch Architects (BNA), one third of the architectural firms have succumbed to the crisis in less than ten months, and the Chief Government Architect has announced an emergency programme to prevent the emergence of a lost generation as a result of the economic depression and the drastic cuts that are taking place in the building sector.

The architecture in this book has little in common with typical Dutch architecture in this sense, neither does it have any connection with an emergency programme. Its aim is nothing less than to be a radical part of the solution. This architecture presents solutions to questions that are both much larger than architecture and impossible to tackle without architecture. This architecture is not about the desired form or the possible analysis. It is above all about necessity, about architecture’s capacity to resolve pressing problems. This architecture is not distracted by the current market situation, in which the question is whether there is work for architects. It is about a vision of the future and the focus that is required to keep that picture sharp. So it is also about the speculative minds of architects young and old which are essential for a vision of this kind and about their design research.

This book begins and ends beyond architecture, presenting a unique opportunity for architecture today, the rediscovery of a social necessity that consistently produces worthwhile architecture. Such moments are historically rare. They occur only when the old procedures are no longer adequate and the new ones have not yet arrived on the scene. This crisis is too valuable an opportunity to let slip by, a chance to turn back to where architecture starts, in the creative spatial organisation of life – not in style choices or concept analyses, but in the identification of new spatial constellations; not in the spatial allocation and accommodation of a given programme, but in helping to create a spatial organization for multiple programmes; not in making things in space, but in organizing processes in time; in short, not in the object, but in performance. This architecture is not about superficial beauty, but about results. Eventually, architecture turns out to be an unparalleled field of innovation.

This insight probably comes as a surprise to the reader. Anyone who explores contemporary theories of innovation will soon notice that expectations about future social breakthroughs and thus future economic prosperity are mainly concentrated on high tech: information technology, biotechnology, nanotechnology and neurotechnology. In other words, bits, genes, atoms and neurons. That is where the vast resources for research are concentrated, where social relevance and social respect are located. Nobody in this global knowledge field is still betting on architecture – the profession of stones, soil, space and slowness. Nether is it logical to expect that breakthroughs in the technologies mentioned above will have immediate architectural outcomes as earlier technological revolutions did: the church, the palace, the factory, the station, the bank. How can architecture today benefit from progress in genetics and nanotechnology? Architecture is not just suffering from an economic crisis but also threatened by a crisis of motivation. If that lasts too long it will be faced with a crisis of talent too.

What can architecture do to avert this scenario and unite its social role in the present with its future mission? Simply put, it must start with what is necessary. More than any new technology the old technology of architecture provides solutions to problems associated with food chains, healthcare, energy flows, lack of space, time management, social tensions and the present economic system.

What is needed is a spatial organization that allows people to achieve self-sufficiency again, that constructs healthier environments, that produces energy rather than merely consuming it, that does not cost space or time but creates them, that promotes cohesion, a spatial organization whose value is defined as a unified process of design, building and maintenance. This is an assignment with the appeal of an Apollo project, or, in the Dutch experience, the symbolic force of the Delta works project. Architecture has been presented with an opportunity that is seldom available.

An architecture that focuses on the many possibilities of intensification and combination is a realistic proposal. Rather than an architecture of monoprogrammatic zones, single issue spaces, zoning plans and highly individual, unrepeatable statements, it would be an architecture that derives sustainability from the sharing of space, services, energy, transport, the public domain and of values, an architecture that through that sharing achieves wholly new typologies.

This book is full of examples of that kind of architecture, from CO2-neutral to energy-producing buildings and landscapes, from high-quality architecture for lower income groups to a villa made from refuse, from temporary hotels in demolition zones to the redevelopment of existing social housing, from unique business alliances at the regional level to cooperative, productive teams involving local residents.

Architecture is already presenting this vision for the future, as this book demonstrates. The architects presented here, though often rivals in daily life, display a striking unanimity in their ambitions for their profession. Theirs is not a pact or movement in which all noses have to point in the same direction, but rather a competition in which the participants are driven by the same innovative motivation – their profession has set out to solve the problems it helped create.

Visions of the future, images to lend force to that vision, strategies for getting there, the force of conviction to follow those strategies can all be found in this book. The only thing missing is effective implementation by decision makers. We hope that this book will help to find them. (Introduction Essay of the catalogue of the exhibition „Architecture of Consequence“, Rotterdam 2009)

Einleitender Essay zum Katalog der Ausstellung „Architecture of Consequence“, 2009. Übersetzt von Sigrid Szabó

Werkstatt

Jo Coenen als niederländischer Reichsbaumeister

Der aus Maastricht stammende Jo Coenen steht einer Institution vor, die in der Welt ihresgleichen sucht. Er ist nämlich Reichsbaumeister der Niederlande und damit mitverantwortlich für die staatliche Architekturpolitik. Die einzigartige Stellung der niederländischen Architektur im internationalen Kontext ist also keineswegs zufällig.

Die Maastrichter müssen ein glückliches Völkchen sein. Die Stadt hat sich eine beschauliche Atmosphäre erhalten, von der sie besonders an Sommertagen zehrt. Schnell füllen sich dann die Strassencafés des Vrigthof-Platzes, und während man sich im Schatten der Sant Servaas Kerk verwöhnen lässt, kommt das Gefühl auf, in längst vergangene Zeiten versetzt zu sein. Kaum zu glauben, dass nur einen Steinwurf entfernt einer der eigenwilligsten Architekten der Niederlande in einem herrschaftlichen Altbau sein Atelier eingerichtet hat. Jo Coenen ist vieles in einer Person: Hochschullehrer, Architekt, Stadtplaner - und Reichsbaumeister. Als solcher ist er mit den höchsten planerischen Aufgaben betreut und berät die Regierung in ihren Entscheidungen.

Bevor Coenen vor zwei Jahren in die oberste Bauinstanz des Landes gewählt wurde, hatte er sich als Architekt einen Namen gemacht. So baute er 1993 in Rotterdam den Neubau des renommierten Niederländischen Architektur-Instituts (NAI), in welchem die einzelnen Gebäudeteile auf Kollisionskurs zu gehen scheinen. Impulsgebend sind auch spätere Projekte: Im Düsseldorfer Medienhafen vollendete er kürzlich einen 16-geschossigen Büroturm mit Fassaden aus Muschelkalk und Glas, der wie ein Ausrufezeichen am südlichen Ende des Hafenbeckens steht. Und auf dem Amsterdamer Oosterdok-Eiland errichtet er zurzeit eine «Stadtbibliothek». Aber Coenen besteht darauf, dass er sich neben seiner Tätigkeit als Architekt immer auch als Stadtplaner verstanden hat.

Funktionsmischung

So erstellte er für das unweit der Maastrichter Altstadt gelegene Industriegelände von «Sphinx Céramique» einen Masterplan mit einer Funktionsmischung aus Wohnen, Arbeiten, Freizeit und Kultur, für den er international anerkannte Kollegen an die Maas holen konnte. Vertreten ist sein Tessiner Lehrer Luigi Snozzi, der entlang des Ufers Apartmentblocks wie Waben aneinander reihte. Mario Botta bewies mit «La Fortezza» ein weiteres Mal seinen Hang zu festungsartigen Backsteinarchitekturen, Wiel Arets verlieh dem «Indigo Office Building» eine markante Fassade mit Fensterbändern, und Alvaro Siza baute neben sein Turmgebäude eine sichelförmige Anlage für Wohnungen und Büros. Vor ihnen hatte schon Aldo Rossi mit dem Bonnefanten-Museum ein Wahrzeichen errichtet. Schliesslich hat auch Coenen auf dem Areal gebaut. Am eindrucksvollsten gelang ihm dabei die Renovierung eines Theaterhauses und der Anbau eines Cafés, von dessen Terrasse der Blick bis zur Maas schweift.

Im Gespräch erzählt Coenen von seinem ersten Grossprojekt, dem Masterplan für die KNSM- Halbinsel am Amsterdamer Hafen, mit dem er den öffentlichen Raum der Stadt reaktivieren wollte. «Anders als in unseren Nachbarländern gibt es in den Niederlanden Politiker und Bürger, die noch immer Wert auf öffentliche Plätze legen.» Wenn man heute durch die fast menschenleeren Strassen der einstigen Hafenmole geht, versteht man schnell, dass auf KNSM und den benachbarten Halbinseln Java, Borneo und Sporenburg allzu sehr auf verdichtetes Wohnen gesetzt wurde - zulasten einer lebendigen Funktionsmischung. Es dauerte einige Jahre, bis sich die Hafenfront belebte durch die Cafés, Restaurants und Geschäfte in Kollhoffs «Piräus»-Gebäude und im «Hofhaus» von Diener & Diener. Nun aber, in seiner neuen Funktion als Reichsbaumeister der Niederlande, möchte Coenen alles besser machen. Nach seinem Amtsantritt vor zwei Jahren verliess er die beengten Räume des Ministeriums und zog mit einer kleinen Gruppe von Mitarbeitern in ein grösseres Gebäude in Den Haag um. «Mir ist die räumliche Distanz zur Regierung wichtig, denn es ist ja meine Aufgabe, das Kabinett bei Bauaufgaben kritisch zu beraten.» Kurz darauf kam der Paukenschlag: Der neue Reichsbaumeister Coenen veröffentlichte eine Programmschrift mit dem Titel «Die Niederlande gestalten». Diese «Nota» stellte klar, welchen Richtlinien die staatliche Baupolitik in den nächsten Jahren folgen soll.

Der erste Satz beruhigte zwar noch die Gemüter durch den Hinweis auf das internationale Ansehen der niederländischen Architektur, doch dann heisst es: «Der Schwund öffentlicher Räume ist besorgniserregend, Wohnsiedlungen wuchern über die Grenzen von Städten und Dörfern.» Gleichzeitig sei die Qualität der öffentlichen Räume in den Städten so erschreckend, dass «die Niederländer sich wie zusammengepfercht» fühlen. Die erste, vor zwölf Jahren verabschiedete Nota zu «Raum für Architektur» setzte die Bedingungen für bauliche Qualität fest, während die folgende Nota von 1996 («Architektur des Raums») Richtlinien für die städtische Entwicklung und den Landverbrauch vorgab. Coenen erklärt, dass die neue Nota die früheren weiterführe, sich aber auch deutlich von ihnen unterscheide: «Wir müssen uns mit der gesamten gestalterischen Skala beschäftigen - von der Anfertigung eines Stuhls bis zum Städtebau, von der Stadt- bis zur Regionalplanung.»

Langfristige Konzepte

In seiner Nota «Die Niederlande entwerfen» möchte Coenen verschiedenste Fachkräfte zusammenbinden, um die gegenwärtige «Krise der Architektur» zu überwinden. Man versteht, dass Coenen die Herrschaft von Spezialisten entschieden ablehnt: «Wenn ästhetische Fragen im Vordergrund stehen, dann wird die Architektur zusehends eingeschränkt, und der Beruf verliert seinen Sinn.» Am liebsten möchte Coenen die Entscheidungen aus den Händen der Baukoordinatoren und Manager nehmen und sie wieder denen übergeben, die weniger durch das Schielen nach hoher Rendite als durch entwerferisches Denken geleitet werden. Um seinem Anspruch Nachdruck zu verleihen, machte Coenen zehn «Grosse Projekte» zum Kern seiner Architekturnota. So verschieden diese Projekte anmuten, wollen sie doch «eine ästhetisch anspruchsvolle Mischung aus Architektur, Infrastruktur und Landschaft» erreichen. «Delta Metropolis», das wohl anspruchsvollste Projekt, verfolgt die Umwandlung des fragmentierten Lebensraums Randstad in ein kohärentes urbanes System bei gleichzeitiger Verbesserung der Verkehrswege. Andere Projekte sehen die Erweiterung des Amsterdamer Rijksmuseum durch die Sevillaner Cruz und Ortiz oder den Schutz öffentlicher Stadträume vor rücksichtslos agierenden Developern vor.

«Wir sind dabei, die Niederlande neu zu gestalten», bekennt Coenen selbstbewusst. Er, der Professor für «Gebäudelehre und Entwerfen» an der TU Karlsruhe und später Gastprofessor in Aachen war, weiss sehr wohl, dass die niederländische Architekturpolitik klare Vorzüge besitzt. Versucht die Regierung doch möglichst viele langfristige Konzepte für die Zukunft des Landes voranzutreiben. Allein die Vielzahl von lokalen, regionalen und staatlichen Architekturzentren befruchtet die Diskussionskultur. Coenen erinnert beispielsweise an die Debatte anlässlich der Nota «Belvedere», die darauf zielte, die Wucherung der Städte einzudämmen und den Wert der Landschaft neu zu bestimmen. Die Anteilnahme an dieser Diskussion, so Coenen, sei vergleichbar gewesen mit der Breitenwirkung der IBA Emscherpark, die innerhalb von zehn Jahren das industriell geprägte Ruhrgebiet in einen vollkommen neuen Kulturraum transformiert habe. Für ihn machen die Diskussionen der Notas deutlich, dass Architektur jeden angehe. «Deswegen steht die Tür meines Ateliers jedem offen. Es ist doch eine wunderbare Einrichtung, wenn das Entwurfsatelier eine Verlängerung der Strasse ist. Jeder kann hereinkommen.»

Holländische Bahnbauten im NAI

An das System europäischer Hochgeschwindigkeitszüge sind die Niederlande bisher nicht angeschlossen. In den nächsten zehn Jahren wird sich das ändern mit einer Nord-Süd-Linie von Amsterdam über Rotterdam nach Brüssel (Eröffnung 2005) und einer West-Ost-Verbindung über Utrecht Richtung Düsseldorf (2010). Eine Querverbindung nach Hamburg könnte schliesslich die Hansestadt zum 90 Minuten entfernten Vorort werden lassen. Diese Erfolgsmeldungen wären noch kein Anlass für eine Ausstellung des Nederlands Architectuurinstituut in Rotterdam; aber die Holländer versuchen, aus Versäumnissen anderer zu lernen und das ambitionierte Projekt nicht allein unter dem Primat planungsrechtlicher oder ökonomischer Kategorien durchzusetzen. Gewiss, man ist spät auf den Zug aufgesprungen, doch scheinen die niederländischen Architekten und Planer mit viel Realitätssinn und Pragmatismus das Entwicklungspotential der Städte und infrastrukturelle Innovation zu verbinden. So dürfte Ben van Berkels Bahnhofprojekt für Arnhem, das sich derzeit im Rohbau abzuzeichnen beginnt, zu einem Meilenstein der Verkehrsarchitektur avancieren. Benthem Crouwel wurden mit Brückenbauten beauftragt, Pi de Bruijn entwirft ein neues Zentrum am Bahnhof Amsterdam Süd, und MVRDV erarbeiten eine Studie zur Umgestaltung der Centraal Station von Amsterdam. Mobilität, so liess Rijksbouwmeester Wytze Patijn verlauten, sei heutzutage eines der wichtigsten Themen im Städtebau. Einen Überblick über die zukünftigen Bahntrassees sowie die wichtigsten Projekte gibt die Ausstellung - durchaus passend zum Thema - auf Informationsträgern in Form von Werbetafeln und Baustellenschildern.

[ Bis 2. Januar; Broschüre (niederländisch) hfl. 6.75. ]

Ein Gespräch mit dem Rotterdamer Landschaftsplaner Adriaan Geuze

Unter dem Namen «West 8» stellte Adriaan Geuze, einer der wichtigsten Erneuerer der Landschaftsarchitektur, 1987 ein Team zusammen, das die unterschiedlichsten Aufgaben gelöst hat: vom Masterplan für Borneo-Sporenburg in Amsterdams altem Hafen bis zum Schouwburgplein in Rotterdam. Klaus Englert sprach mit Adriaan Geuze.

Wie kamen Sie zur Landschaftsarchitektur?

Wir machten uns nie Illusionen über Landschaftsarchitektur. Statt dessen gingen wir davon aus, dass in der heutigen Kultur architektonische Entwürfe, Ökologie, Stadtplanung und Industriedesign nicht voneinander zu trennen sind.

Sehen Sie einen Unterschied zwischen traditioneller Landschaftsarchitektur und Ihrer Arbeit?

Dieser Unterschied ist offensichtlich, und er beruht auf verschiedenen geistigen Voraussetzungen. Der Ursprung der heutigen Disziplin geht auf die romantische Landschaftsarchitektur zurück, auf Leute wie Frederick Law Olmsted, der in den Vereinigten Staaten arbeitete. Später, im 20. Jahrhundert, wurde die romantische Ideologie besonders in der deutschen und der skandinavischen Landschaftsarchitektur durch eine anthroposophische Komponente ergänzt. Der Leitgedanke war: Die Stadt ist schlecht und die Natur gut. In den zwanziger Jahren setzte man auf geistige und sportliche Rekreation in Grünanlagen und Parks. In den sechziger Jahren, in der Zeit der Hippies und des «Club of Rome», wurde über die Ausbeutung des Planeten Erde diskutiert. Dies führte dazu, dass die Natur als etwas grundsätzlich Gutes betrachtet wurde.

Wie ist diese Sicht mit der holländischen Tradition der Landgewinnung zu vereinbaren?

Die Holländer hatten stets auf die Natur eingewirkt. Aus dieser Tradition heraus habe ich einen starken Widerwillen gegen die romantische Landschaftsarchitektur entwickelt. Meine Professoren erzählten mir, dass die Menschen vor allem Opfer seien - Opfer der Stadt, des Verkehrs und des Kapitalismus - und dass die Landschaftsarchitektur einen Ausweg aufzeigen müsse. Ich meine jedoch, dass die Menschen keineswegs Opfer, sondern gut informierte und schöpferische Wesen sind - auf der Höhe der technologischen Entwicklung. Das bedeutet nicht, dass sich die Landschaftsarchitektur gegenüber ökologischen Anliegen gleichgültig verhalten sollte.

Eine neue Landschaftsarchitektur

Welche persönlichen Erfahrungen führten zu Ihrem Verständnis von Landschaftsarchitektur?

Zu meiner Studienzeit war die akademische Lehre vergiftet. Ausschlaggebend war nicht allein das romantische Reservoir, auch nicht der deutsche Naturkult der zwanziger oder die Hippie-Bewegung der sechziger Jahre, sondern die Verbindung aller drei Strömungen. Leider wurden diese Dogmen niemals offen artikuliert, weswegen es schwierig war, sie zu bekämpfen. Für mich kam eine weitere Erfahrung hinzu: Vor zwanzig Jahren, zur Zeit des wirtschaftlichen Umbruchs, entstand ein riesiges Arbeitslosenheer, und zum ersten Mal wurde der politische Wunsch geäussert, eine Million Häuser innerhalb von zehn Jahren zu bauen. Es stellte sich schnell heraus, dass der Wildwuchs der Städte schwindelerregende Ausmasse annahm. Anstatt Ballungszentren und Uferlinien zu nutzen, brachte die Stadtplanung Krebsgeschwüre ohne funktionierende Infrastrukturen hervor. Also fragte ich mich: «Warum gestalten die Landschaftsarchitekten Parks, statt sich mit diesen Fragen auseinanderzusetzen?»

In welche Richtung sollte sich denn die Landschaftsarchitektur weiterentwickeln?

Seit den sechziger Jahren gibt es interessante Untersuchungen über unser Verhältnis zu Parks und zur natürlichen Umgebung. Sie haben ergeben, dass viele Menschen eine unmittelbare Konfrontation mit der Natur, die sie für gefährlich und unordentlich halten, möglichst vermeiden. Das Problem in meinem Land besteht darin, dass wir zu viele Grünanlagen haben und dass die Möglichkeit ausreichender Pflege kaum besteht. Wir brauchen mehr geschlossene Gartenanlagen, die zu Galerien, Museen oder Kirchen gehören. Deren Besitz und Unterhalt ist zwar privat, aber ihre Nutzung mehr oder weniger öffentlich.

Sehen Sie Unterschiede zur Landschaftsarchitektur in Deutschland oder in der Schweiz?

Es bestehen vollkommen verschiedene Voraussetzungen, weil die vor zwanzig Jahren begonnene Suburbanisierung die gesamten Niederlande nachhaltig ruiniert hat. Heute sind wir mit den Auswirkungen dieser Entwicklung konfrontiert.

Und wie begegnet man dieser Entwicklung auf der politischen Entscheidungsebene?

Das grundsätzliche Problem in den Niederlanden besteht darin, dass die einzelnen Gemeinden zu viel Macht besitzen und ihr eigenes Programm durchsetzen wollen. Dieses deregulative System bedingt, dass jede Stadt eine eigene Autobahnausfahrt besitzt, ein Business-Center und einen McDonald's. Das ist für ein kleines Land wie die Niederlande katastrophal. Deshalb machten wir den Vorschlag, die Regierungen auf regionaler Ebene zu stärken. Dies wird Auswirkungen auf die Randstad Holland haben, wo fünf Millionen Menschen, verteilt auf achtzig bis neunzig Gemeinden, leben.

Ist demnach das System Randstad mit seinen urbanen Wucherungen gescheitert?

Die holländische Stadtplanung hat viele Fehler gemacht. Vor dreissig Jahren wurden im sozialen Wohnungsbau Menschen in Hochhäuser eingepfercht, und später, als man die Probleme erkannte, wurden die Häuser in die Luft gesprengt. Heute sind die Fehler nicht minder gravierend. Man meint das Ei des Kolumbus in der angeblichen Vitalität suburbaner Siedlungen gefunden zu haben. Doch diese Suburbs haben weder eine städtische Dichte noch eine ländliche Atmosphäre, sie sind ein unsinniges Zwischending.

Modell Amsterdamer Hafen

Bedeutet das städtebauliche Konzept für Borneo-Sporenburg im Amsterdamer Hafen einen Ausweg aus dem Dilemma der Suburbanisierung?

Auf Borneo-Sporenburg wollten wir zeigen, dass Modelle mit einer höheren Dichte besser funktionieren. Wir haben hier eine Dichte von hundert Häusern pro Hektare und gleichzeitig eine niedrige Bebauungshöhe geschaffen, weshalb das Projekt als Alternative zu den bestehenden Vorstädten und als Testfall für neue Typologien gesehen werden kann. Es gilt aber sehr genau zu untersuchen, wie sich die sozialen Strukturen dem architektonischen Umfeld anpassen. Für Borneo-Sporenburg erstellten wir einen Plan, der eine grosse architektonische Vielfalt zuliess, was für die Niederlande absolut einzigartig ist. Während Typologie und Baumaterialien vorgeschrieben wurden, gab es keine Einschränkung der architektonischen Freiheit - so wie beim Amsterdamer Grachtenhaus, das zwar in der Bauweise kaum Unterschiede aufweist, aber doch einen grossen Spielraum für individuelle Gestaltung freilässt. Ein Glücksfall kam hinzu: Die Marine gestattete uns, die sehr regulierten Siedlungseinheiten durch die einer alten Amsterdamer Tradition entsprechende Nutzung der Quais zu beleben: Leute kommen mit ihren Hausbooten und ihren verrückten Ideen und bringen ein anarchistisches und künstlerisches Element ins neue Quartier.

Den Architekten in den Niederlanden scheint es gut zu gehen.

Man könnte meinen, dass wir uns in den Niederlanden im goldenen Zeitalter der Architektur befinden, weil viele junge Architekten radikal Neues bauen. Dabei wird ein wesentlicher Aspekt übersehen: Durch mangelhafte Investitionen und durch fehlende handwerkliche Genauigkeit entsteht alles andere als dauerhafte Architektur. Die holländische Bauindustrie basiert lediglich auf der Massenproduktion von Paneelen, Mauern und Materialien. Deswegen sollte man sich keinen Illusionen hingeben, da die scheinbar so grossartigen Neubauten in hundert Jahren nicht mehr existieren werden.

Cees Nooteboom und die Architektur

Ein beispielhaftes Unterfangen: Man nehme einen Schriftsteller mit Affinität zur Baukunst und bitte ihn, aus einem Konvolut nicht realisierter Entwürfe eine Art architektonischer Weltidee zu formen. So geschehen nun durch Cees Nooteboom, der die niederländische Architekturgeschichte der letzten 150 Jahre auf eigenwillig- suggestive Weise Revue passieren lässt. Nootebooms «Nie gebaute Niederlande» will zeigen, dass diese Region ganz anders hätte aussehen können. So banal diese Botschaft klingen mag, so faszinierend ist sie bei näherem Hinsehen. Denn das Buch manifestiert zugleich auch, wie dieses Land einst ausgesehen hat. Selten sei, wie Nooteboom zur Begründung dieses Paradoxes anführt, «Wünschen, Sehnsüchten, Ideen und Träumen so klar und übergenau Ausdruck verliehen worden wie in der nicht gebauten Architektur».

Offeriert wird von Nooteboom eine Art apokrypher Historie: So blieb beispielsweise das Neue Museum in Amsterdam von L. H. Eberson deshalb ungebaut, weil es nicht einem «niederländischen» Stil, sondern der Formensprache von Louis XVI verpflichtet war. Nootebooms Beispiele reichen von W. C. Bauers Wettbewerbsentwürfen, in denen byzantinische und islamische Architekturelemente aufscheinen, über das Allgemeine Bibliotheksgebäude von K. P. C. de Bazel (1895) bis hin zu Berlages Projekt eines Beethovenhauses in Bloemendaal (1908). Dass auch unrealisierte Bauten den Beschauer manipulieren können, offenbaren zu Beginn der zwanziger Jahre die expressiven Wolkenkratzergebilde eines J. C. van Epen sowie die an die Revolutionsarchitektur eines Ledoux und Boullée angenäherte Vision einer Lichtstadt von H. P. J. London.

Spätestens hier erreicht der Spannungsbogen den Nährboden der klassischen Moderne: J. J. P. van Oud konzipierte 1919 in Purmerend eine Fabrik mit Büros und Magazinen, die das, was Mondrian im Zweidimensionalen realisiert hat, in den Raum zu übersetzen trachtete. Rietvelds «Kernwohnungen» (1940) gehorchten der Not und Van den Broeks und Bakemas Pampusplan für Amsterdam (1964/65) dem Geist der Zeit. Die Parlamentserweiterung von OMA (Rem Koolhaas mit Zaha Hadid, 1977) und das Einkaufszentrum Z-Mall in Leidschenveen (1997) von MVRDV mit der einer Ziehharmonika ähnelnden Baustruktur runden die subjektive Palette an Papier gebliebener Architektur ab. Eine beredte und bildmächtige Geschichte im Konjunktiv - wenn all dies nicht ungebaut geblieben wäre, dann, so Nooteboom, würde es auf uns einwirken wie alles andere um uns herum. Umso verführerischer, all dies durch die Brille des Literaten zu erblicken. Denn «im nicht Gebauten sehen wir uns, wie wir nicht geworden sind».

[ Cees Nooteboom: Nie gebaute Niederlande. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, München 1999. 120 S., Fr. 46.-. ]

Wright und die Niederlande - eine Ausstellung in Hilversum

Seit 1911 standen niederländische Architekten im Banne Frank Lloyd Wrights. Nirgendwo sonst hatte der amerikanische Baumeister einen so starken Einfluss wie zwischen Rhein und Nordsee. Eine Ausstellung in Hilversum dokumentiert die Rezeption in all ihren Facetten.

Ein grossformatiges Portfolio und eine handliche Publikation der Bauten von Frank Lloyd Wright, die der Berliner Verlag Ernst Wasmuth in den Jahren 1910 und 1911 herausbrachte, lösten in europäischen Architektenkreisen nachhaltige Begeisterung aus. Zwar hatte der Engländer Charles Robert Ashbee seinen amerikanischen Kollegen schon 1901 besucht, doch blieben Wrights Bauten diesseits des Atlantiks vorerst weitgehend unbekannt. Doch seit dem Erscheinen der Wasmuth-Publikation, zu der Ashbee ein Vorwort beigesteuert hatte, galten sie als Offenbarung: in Deutschland, wo sie Peter Behrens, Walter Gropius und Mies van der Rohe faszinierten, vor allem aber in den Niederlanden. Hendrik Petrus Berlage, der Wegbereiter der niederländischen Architektur des 20. Jahrhunderts, reiste damals in die Vereinigten Staaten; er versäumte Wright, der sich gerade in Berlin aufhielt, besuchte aber eine Reihe von seinen Bauten. Frucht seines Aufenthalts waren eine Reihe von Vorträgen und Veröffentlichungen, welche Frank Lloyd Wrights Bekanntheit in den Niederlanden weiter steigerten.

Publikationen und Adaptionen

Schnell wurden die Bauten des Amerikaners in den Niederlanden zitiert, kopiert und adaptiert. Die Breite und Vielfalt der Rezeption wurde nicht zuletzt dadurch begünstigt, dass das Land im Ersten Weltkrieg neutral blieb und das Bauwesen - anders als in den kriegführenden Ländern - eine regelrechte Blüte erlebte. Landhäuser in den Heide- und Dünengebieten entstanden nach dem Vorbild der Präriehäuser, die aufgrund der Verwendung von Backstein, der luxuriösen Innenausstattung und der Verzahnung von Architektur und Landschaft ein favorisiertes Vorbild darstellten. In Berkel-Enschot baute der Architekt F. A. Warners das Robie House nach, und zu den bekanntesten Adaptionen zählen zwei Villen des ebenfalls in die USA gereisten Robert van't Hoff in der Ortschaft Huis ter Heide: das Haus Verloop mit seinen typischen, breit gelagerten Dächern (1915) und die symmetrische, flachgedeckte Villa Nora (1916), die an das Thomas Gale House (1909) in Oak Park und das Bach House in Chicago (1915) erinnert.

«Dromen van Amerika - Nederlandse Architecten en Frank Lloyd Wright» heisst die reich bestückte Ausstellung, mit der im Museum Hilversum die Beziehungen zwischen dem Amerikaner und seinen niederländischen Bewunderern nachgezeichnet wird. Eine Chronologie von Leben und Werk Wrights an den Wänden bildet den Hintergrund, vor dem auf Podesten und in Tischvitrinen Dokumente der Rezeption ausgebreitet sind. Die Kenntnis des uvres wurde besonders durch Hendrik Theo Wijdeveld gefördert, der als Herausgeber der Zeitschrift «Wendingen» 1921 Kontakt mit Wright aufnahm. Das Novemberheft 1921 wurde diesem gewidmet, eine Doppelnummer im Jahr 1923 - und schliesslich die berühmte Sequenz von sieben aufeinander folgenden «Wendingen»-Heften im Jahr 1925. Es war wiederum Wijdeveld, der 1931 die erste europäische Ausstellung Wrights an das Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam vermittelte; für eine zweite Schau am gleichen Ort zeichnete 1952 J. J. Oud verantwortlich. Als einziger Entwurf Wrights, der in den Niederlanden umgesetzt wurde, gilt eine grüne Pressglasvase für die Königliche Glasmanufaktur Leerdam - in der Ausstellung sind auch zwei nicht realisierte Prototypen zu sehen.

Zur romantisch grundierten Rezeption des Wright der Präriehäuser trat schon in den ersten Jahren eine eher rationale Aneignung. So übernahm K. P. C. de Bazel die offene, von Pfeilern gegliederte Bürostruktur des auch von Berlage bewunderten Larkin Building für das Gebäude der Nederlandse Heidemaatschappij in Arnheim (1912). Rechtwinklige Volumina, vor- und zurückspringende Flächen sowie die Betonung horizontaler und vertikaler Elemente bestimmten die Entwürfe vieler Architekten in den zehner und zwanziger Jahren, vor allem jene der Stijl-Gruppe. In den Bauten von Jan Wils, etwa in dem Café De Dubbele Sleutel (1918/19) in Woerden, wird die Wright-Nachfolge besonders deutlich; purifizierter zeigen sich neoplastizistische Kompositionen wie die Villa Sevensteijn (1920) von Dudok und Wouda oder der nicht realisierte, an die Midway Gardens in Chicago angelehnte Entwurf für eine Schule in Scheveningen von Jan Duiker (1921-28).

Gescheiterte Visionen

Persönlich kamen Wijdeveld und Wright 1931 in Taliesin in Kontakt. Beide trugen sich mit der Idee einer künstlerischen Werkgemeinschaft, und Wijdeveld war als Direktor der Hillside Home School of Applied Arts and Industries vorgesehen. Doch die Idee einer Zusammenarbeit zerschlug sich; Wright gründet 1932 die Taliesin Fellowship, Wijdeveld plant, sein kulturelles Zentrum gemeinsam mit Mendelsohn und Ozenfant in Südfrankreich zu realisieren. Ein Waldbrand auf dem avisierten Terrain zwingt Wijdeveld zurück in die Niederlande, bevor das Projekt angelaufen ist; ein zweiter Versuch in Elckerlyc bei Hilversum scheitert wegen der deutschen Besatzung 1940. Ohne Erfolg bleibt 1950 auch der Versuch, Elckerlyc als Kooperation mit Taliesin durch Unesco-Mittel zu finanzieren.

Mit dem Siegeszug der internationalen Moderne nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg liess die Orientierung an Frank Lloyd Wright auch in den Niederlanden nach. Eine gewisse Verbindung bestand hinsichtlich des Umgangs mit Innen- und Aussenräumen bei den Strukturalisten Hertzberger, Blom und van Eyck; und Hugh Maaskant realisierte in Mijdrecht eine Filiale der Firma Johnson Wax, deren berühmter Hauptsitz in Racine (Wisconsin) von Wright stammte. Die Ausstellung klingt aus mit einem Hinweis auf die «Superdutch»-Architektur von OMA, MVRDV oder UN-Studio: Die heutigen Architekten, so die These, bezögen sich hinsichtlich ihrer internationalen Wirkung und ihres Star-Status auf den Amerikaner, der schon mit dem durch King Vidor verfilmten Roman «The Fountainhead» zum Rollenmodell des modernen Architekten avanciert war.

Wright in Amsterdams Arkadien

Anschliessend an einen Besuch der Ausstellung empfiehlt sich eine Fahrradfahrt durch das inmitten von Heidelandschaften gelegene Hilversum. Mit weitläufigen Villengebieten wurde das einstige Dorf im 19. Jahrhundert zum Arkadien von Amsterdam. Von der Wright-Rezeption vor Ort zeugen Villen von Jan Wils (1929) am Simon-Stevin-Weg, aber auch die bemerkenswerte Emma- Apotheke (1921) von Rueters und Symons. Wie kein anderer Architekt aber hat Dudok das Stadtbild von Hilversum geprägt - vor allem mit dem Rathaus und zahlreichen Schulgebäuden. In vielen seiner Bauten ist der Einfluss Wrights offensichtlich, auch wenn Dudok diesen zeitlebens verneint hat.

[ Bis zum 4. Juni im Museum Hilversum. Begleitbroschüre Euro 7.50. ]

Neumittelalterliche Architektur an Rhein und Maas

In Architektenkreisen gelten die Niederlande als Vorposten der zeitgenössischen Baukunst. Doch ausgerechnet hier feiert eine spätpostmoderne Architektur neue Triumphe: Wohnanlagen haben die Form von Kastellen, und eine Siedlung bei Helmond entsteht in den Formen einer brabantischen Kleinstadt aus dem 17. Jahrhundert.

Gemeinhin gelten die Niederlande als Musterland der zeitgenössischen Architektur. Die Bauten von UN Studio, Mecanoo oder Wiel Arets, die Projekte von MVRDV und NOX finden international Beachtung, viele prominente niederländische Architekturbüros sind inzwischen weltweit tätig, und in Rotterdam konnte Rem Koolhaas, ohne dessen Wirken der Boom des «Superdutch» kaum zu erklären wäre, unlängst im Vorfeld seines sechzigsten Geburtstags mit zwei Ausstellungen einen umfassenden Überblick über sein Gesamtwerk geben (NZZ 15. 4. 04). So wichtig die architektonischen Impulse auch sein mögen: Eine vorbehaltlose Idealisierung der niederländischen Baukunst ist schwerlich angebracht. Die Zersiedelung des Landes schreitet voran, und es sind keineswegs die aus Fachzeitschriften bekannten spektakulären Gebäude, welche das Bild prägen, sondern Bauten ohne jeden gestalterischen Anspruch. Daneben ist zu konstatieren, dass kaum einer der Protagonisten, welche für die Boomphase der niederländischen Architektur stehen, an inländischen Fakultäten unterrichtet. Am meisten aber überrascht eine neotraditionalistische Architektursprache, die sich zurzeit im Land grosser Beliebtheit erfreut.

Neue Burgen

In formaler Hinsicht läutete das innerstädtische Revitalisierungsmodell «De Resident» in Den Haag, mit dessen Planung 1988 begonnen wurde, den Retro-Trend ein. Zwischen dem Zentralbahnhof und dem Stadthaus von Richard Meier ist in den vergangenen Jahren nach einem Masterplan von Rob Krier sowie unter Mitwirkung von Sjoerd Soeters und Michael Graves ein innerstädtisch verdichteter Büro- und Wohnkomplex in bizarren spätpostmodernen Formen entstanden. Gerade in einem Land, das sich als Kunstprodukt zu verstehen schien und dessen architektonische Exponenten die Last des Geschichtlichen überwunden zu haben behaupteten, musste die Vergangenheitsbeschwörung erstaunen. Dies umso mehr, als sich die Postmoderne im internationalen Diskurs diskreditiert hatte, nachdem ihre irrlichternd-ironische Frühphase in der Sackgasse eines radikalen Eklektizismus gescheitert war.

Der zeitgenössische Trend zum Neohistorismus ist zweifellos als Krisenphänomen zu werten. Parallel zu Globalisierung und gesellschaftlichem Wandel restabilisiert sich das vorgeblich Vertraute, auch wenn es lediglich zu synthetischen Bildern gerinnt. Das Phänomen lässt sich in den postkommunistischen Staaten Osteuropas ebenso beobachten wie in den Siedlungen des «New Urbanism» der Vereinigten Staaten; in Deutschland mag man auf das Haus Bastian von Paul und Petra Kahlfeldt oder die Villa Gerl von Hans Kollhoff und Helga Timmermann verweisen, aber auch auf die grassierende Rekonstruktionsmanie.

Wie «De Resident» in Den Haag lehrt, fand der spätpostmoderne Neohistorismus in den Niederlanden sein Betätigungsfeld zunächst bei der Erneuerung der Innenstädte. Adolfo Natalini errichtete in historisierenden Formen nicht nur den Waag-Komplex auf dem kriegszerstörten Marktplatz von Groningen, sondern stampfte in Helmond rund um den Boscotondoplein mit seinen 120 Metern Durchmesser ein kulissenhaftes Plaza-Ensemble aus dem Boden, das aus Kulturzentrum, Bürokomplex, Kinocenter sowie 175 Apartments besteht. Noch erfolgreicher als Natalini ist Rob Krier, der durch seine IBA-Bauten in Berlin bekannt wurde und nach der Wende die Siedlung Kirchsteigfeld in Potsdam realisierte. Der Schwerpunkt des Schaffens von Krier und seinem Partner Christoph Kohl liegt inzwischen in den Niederlanden. Das umfangreichste der zahlreichen vom Berliner Büro aus betreuten Siedlungsprojekte ist Brandevoort bei Helmond, ein vollständig neuer Vorort, in dessen Mitte eine von Wassergräben umgebene «Veste» mit 600 Wohnungen realisiert wird. Tore, Türme und historisierende Ziegelsteinfassaden mit leicht variierenden Traufhöhen sollen das Bild einer mittelalterlichen Kleinstadt Brabants in Erinnerung rufen. Wie in den Niederlanden üblich, wurde der Rohbau in starkem Masse industrialisiert. Individualisierung entsteht durch die unterschiedlichen Fassaden und die - für niederländische Massstäbe - erstaunlich gut ausgeführten Werksteindetails. Brandevoort wirkt nicht billig, sondern steht für Wertbeständigkeit, Tradition und Kontinuität. Mit Geschäften und Schulen wollen die Planer einer monofunktionalen Schlafsiedlung vorbeugen, und in der Mitte der Veste errichten Krier und Kohl eine Markthalle wie aus dem 19. Jahrhundert.

Natürlich ist die autonome dörfliche Stadt eine Illusion, die der Lebenswirklichkeit ihrer Bewohner nicht entspricht. Aber Brandevoort, das auf die obere Mittelschicht zielt, ist äusserst erfolgreich. In Helmond, zu dem die synthetische Siedlung gehört, ist man stolz darauf, vermögendere Schichten in die Gemeinde zurückgeholt zu haben. Die «Veste» in Brandevoort steht nicht allein: In Almere, der geschichtslosen Stadt im Polder des IJsselmeers, lässt ein Projektentwickler eine «echte alte» Burg mit 46 Meter hohem Donjon errichten, die zukünftig als Hotel dient.

Populismus?

Noch bizarrer aber ist das Projekt De Haverleij nördlich von 's-Hertogenbosch: In der Wiesenlandschaft am Maasufer entsteht bis 2008 eine aus neun «Kastellen» und einer «Zitadelle» locker gefügte weitläufige Siedlung mit insgesamt 11 000 Wohneinheiten - gruppiert um einen Golfplatz, dessen Gestaltung ebenso wie das Landschaftslayout von Paul van Beek, einem früheren Partner im Büro «West 8», stammt. Jedes der Kastelle wird von einem anderen Architekturbüro realisiert, darunter Adolfo Natalini, Michael Graves, Claus en Caan und John Outram. Die Planer sehen in ihrem Projekt eine Kampfansage an den Flächenverschleiss der Streusiedlungen; doch nicht zuletzt in ökologischer Hinsicht ist De Haverleij fragwürdig. Eine Anbindung an den öffentlichen Nahverkehr existiert nicht, und unter den «Burghöfen» befinden sich Tiefgaragen.

Erklären lassen sich die neuen Kastelle vor dem Hintergrund der Deregulierung des Wohnungsmarktes in den Niederlanden - und einer politisch veränderten Situation. Der vollständige Rückzug des Staates aus dem sozialen Wohnungsbau Mitte der neunziger Jahre, die Zerschlagung der bisherigen Wohnbauträger und die Verwandlung bisheriger Mieter in Eigentümer lassen die Nachfrage steigen nach Häusern und Wohnungen, die Wertbeständigkeit simulieren. Eine Mittelschicht, die sich von der Gefahr des Abstiegs bedroht sieht, favorisiert ein Leben in Sicherheit - das sich baulich in Form von Festungen und präindustriellen Siedlungsstrukturen darstellt. Nicht ohne Grund fand diese Haltung auf der politischen Ebene Niederschlag im Sieg des Rechtspopulisten Pim Fortuyn, der im Kampf gegen die niederländische Liberalität einen überraschenden Sieg über die etablierten Parteien errang. Zwar ist die Bewegung nach dem Tod des charismatischen Protagonisten marginalisiert, doch der neokonservative Roll-back dauert an: Rotterdam wird inzwischen von «Leevbar Rotterdam» («Lebenswertes Rotterdam») regiert, und «Leevbar Almere» hat unlängst das Projekt für ein Kunstmuseum in Almere platzen lassen, um die Gelder stattdessen in Sicherheitseinrichtungen zu investieren. Der Rezensent des renommierten «NRC Handelsblad» zog daraus in architektonischer Hinsicht folgende Bilanz: Nach den «Fuck the Context»-Gebäuden des Supermodernismus folge nun eine neokonservative «Fuck the Zeitgeist»-Architektur.

Architektur als Ausdruck öffentlichen Kulturinteresses

Die Niederlande haben sich in den letzten Jahren zu einer architektonisch führenden Nation entwickelt. Dies hat sich keineswegs zufällig ergeben. Eine staatlich koordinierte Baupolitik hat viel zu einer besseren Ausbildung, einem starken öffentlichen Interesse an Architektur und einer Planung von Projekten beigetragen, die im nationalen Interesse sind. Holländische Architekten sind absolute Frühstarter: Sie stehen bereits mitten im Berufsleben, wenn etwa ihre Schweizer Kollegen noch fürs Studium büffeln müssen.

Vorzüge der Architekturpolitik

Von der pessimistischen Grundstimmung gegenüber Städteplanung und Architektur in unseren Gegenden sind die Niederländer, ein Volk von technokratischen Machern, weit entfernt. Spricht man beispielsweise den Maastrichter Architekten und niederländischen Reichsbaumeister Jo Coenen auf dieses Problem an, verweist er darauf, dass ein grundlegender Reformwille in seinem Heimatland vieles zum Besseren gewandelt hat. «Wir sind dabei, die Niederlande neu zu gestalten», bekennt er selbstbewusst und zeigt die Programmschrift «Die Niederlande gestalten». Es handelt sich um eine sogenannte Nota, in der ausgeführt wird, welchen Richtlinien die staatliche Baupolitik, unabhängig von den jeweiligen Legislaturperioden, in den nächsten Jahren folgen soll.

Coenen, der viele Jahre lang «Gebäudelehre und Entwerfen» an der Technischen Universität Karlsruhe unterrichtet hat, kennt die klaren Vorzüge der niederländischen Architekturpolitik. So versucht er derzeit, die zehn «Grossen Projekte» voranzubringen. Sie reichen von der Erweiterung des Amsterdamer Rijksmuseum bis hin zur «Delta Metropolis», die die Umwandlung des fragmentierten Lebensraums Randstad in ein kohärentes städtisches System bei gleichzeitiger Verbesserung der Verkehrswege vorsieht. Die Effizienz der holländischen Baupolitik liegt aber nicht einfach in der zentralen Koordinierung durch den Reichsbaumeister, sie resultiert aus der Vernetzung verschiedener Initiativen, seien es lokale, regionale oder staatliche Architekturzentren, deren Zusammenspiel die öffentliche Diskussionskultur wesentlich befruchtet. So konnte die Nota «Belvedere», die darauf abzielte, die Wucherung der Städte einzudämmen und den Wert der Landschaft neu zu bestimmen, einen ähnlichen Erfolg erzielen wie die Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA) Emscherpark, die innerhalb von zehn Jahren das industrielle Ruhrgebiet in einen völlig neuen Kulturraum transformierte.

Piere als Paradiese

Von dieser architektonischen Kultur profitieren selbstverständlich viele in Holland arbeitende Architekten. Beispielsweise der Rotterdamer Adriaan Geuze: Nachdem der Stadtrat in den achtziger Jahren beschlossen hatte, die seit 1979 aufgegebenen Docklands östlich des Hauptbahnhofs zu bebauen, überlegte er, wie das «Oostelijke Havengebied» am Ij revitalisiert und die Stadt näher ans Wasser herangerückt werden kann. Mit Stadtplanern und Investoren setzte Geuze auf die Wiederbelebung der «hollandse waterstad». Auch Jo Coenen war anfangs mit von der Partie. Die beiden erstellten einen Masterplan für die Bebauung einiger Piere, die nicht mehr von Frachtschiffen angelaufen werden.

Coenen war für das erste Projekt, den Wohnungsbau auf der KNSM-Halbinsel, verantwortlich, auf der heute Hans Kollhoffs monumentaler «Piräus-Block» und Wiel Arets' schwarzer Wohnturm wie Landmarken prangen. Geuze widmete sich den Halbinseln Borneo und Sporenburg, wobei er sich an städtischen Konzepten orientierte, die man längst vergessen glaubte: «Im 17. Jahrhundert hatte es in Amsterdam eine hervorragende Stadtplanung hinsichtlich der Strassenführung und der Wasserlinien gegeben. Doch in den fünfziger und sechziger Jahren des letzten Jahrhunderts hatte man jegliche Vorstellung davon verloren, wie eine Stadt gebaut wird. Erst in letzter Zeit kam es zu einer Rückbesinnung auf die alten urbanistischen Vorstellungen des 17. Jahrhunderts. Man versucht nun, das eigene städtische Erbe zu begreifen und wiederzubeleben.»

Adriaan Geuze bewundert Sjoerd Soeters' Bebauung der benachbarten Java-Halbinsel, weil es dort gelungen ist, an die Tradition der Amsterdamer Grachten anzuknüpfen. Aber er weiss, dass dies nicht mit nostalgischer Wehmut, sondern mit einer zeitgenössischen Interpretation der Architektur einhergehen muss. Soeters setzte auf Blockrandbebauung am Ufer und enge Grundstücke an den neuen Grachten, aber jeweils mit einem demonstrativen Individualismus.

Verdichtetes und differenziertes Bauen

Borneo und Sporenburg sind derweil zu einem Paradebeispiel für verdichtetes und differenziertes Bauen geworden. Von langweiligen Reihenhaus- Silhouetten will Adriaan Geuze nichts wissen: «Mich interessiert, dieselben strengen Regeln beizubehalten und doch individuelle Architektur zuzulassen.» Drei Superblöcke, die wie Gletschermassive das ruhige Meer der Wohnhäuser überragen, werden bald die Attraktion der beiden Halbinseln ausmachen. Von den zwei bisher fertiggestellten ist Frits van Dongens «Walfisch», der wie ein gestrandeter Moby Dick aussieht, zweifellos der spektakulärste. Die massiven Blöcke stehen im Kontrast zur niedrigen Gebäudehöhe, die man entlang der Strassen antrifft. Dabei konnte Geuze jegliche Eintönigkeit vermeiden, weil er jedem Architekten gestattete, mit verschiedenen Wohnungstypen zu experimentieren.

Das berühmteste Beispiel ist die Scheepstimmermanstraat auf Borneo, die mittlerweile für viele Architekturbegeisterte zu einem Mekka experimentellen Bauens geworden ist. Hier durften die Architekten ihren ganz eigenen Stil verwirklichen. So errichtete Koen van Velsen für einen holländischen Bergsteiger ein Wohnhaus, dessen gläserne Fronten um einen freistehenden Baum herum angeordnet sind. Anders ging das Rotterdamer Büro MVRDV (Maas, van Rijs, de Vries) vor. Die mittlerweile international bekannten Architekten bieten intelligente Raumaufteilung anstelle kapriziöser Bau-Kunststücke. Ihnen gelang es, extrem engen Grundstücken von 2,5 Metern Breite «das denkbar schmalste Haus» (MVRDV) abzuringen, in dem dennoch räumliche Vielfalt und, dank verglasten Seitenfronten, verblüffende Transparenz geboten werden.

Triumph der Newcomer

Überhaupt sind die Newcomer aus Rotterdam die eigentliche Überraschung in der holländischen Architekturszene. Erst 1999, als sich niemand einen Reim auf das merkwürdige Kürzel MVRDV machen konnte, verblüfften sie alle mit der Sendeanstalt VPRO in Hilversum. Und ein Jahr später debütierten sie auf internationalem Parkett mit ihrem kurios-phantastischen Sandwich-Pavillon für die Expo in Hannover. Auf einmal waren die drei jungen Rotterdamer in aller Munde. Trotz zahlreichen Aufträgen aus dem Ausland ist es ihnen wichtig, weiterhin in den Niederlanden zu bauen, und sogar auf den Amsterdamer Pieren sind sie mit lukrativen, aber höchst unterschiedlichen Projekten vertreten.

Auf der Oostelijke Handelskade renovieren sie erstmals einen denkmalgeschützten Altbau. Das Gebäude, das vor 60 Jahren der Gestapo noch als Internierungslager für Waisenkinder diente, überführt das Rotterdamer Trio derzeit in ein Luxushotel. Ein weiteres Projekt auf dem Silodam ist vor zwei Jahren fertiggestellt worden. Neben zwei ehemaligen Getreidesilos, einer säkularen Backsteinkathedrale und einem Speichergebäude im kargen «Béton brut»-Stil der fünfziger Jahre setzten sie ihr «Containerschiff» ans Kopfende des Silodams. Eine niederländische Tageszeitung titelte damals: «Ein hipper Ozeandampfer, klar zum Auslaufen». Und tatsächlich, der «Dampfer» mit seinen gestapelten Wohncontainern ragt mit seinen wuchtigen Stelzen aus dem Hafenbecken heraus. Weil MVRDV für jeden einzelnen «Container» individuelle Wohnungstypen entwickelte, deren Fassaden durch unterschiedliche Farben hervorgehoben sind, wirkt die knallbunte Schachtel aus dem Experimentallabor des Rotterdamer Avantgarde-Büros wie eine Farbattacke auf die Nüchternheit der sie umgebenden Hafenlandschaft.

Rotterdam gegen Amsterdam

Frits van Dongen, der sein Büro im Amsterdamer Jordaan-Viertel hat, profitierte in den letzten Jahren von der Umnutzung des Amsterdamer und des Rotterdamer Hafens. Beispielsweise errichtete er in Rotterdams «Kop van Zuid», dort, wo internationale Stars wie Renzo Piano und Norman Foster ihre modernen Landmarken an der Maas hochzogen, den Wohnblock «De Landtong» und machte die zuvor verpönte Blockbebauung wieder populär. Auf die lange Rivalität zwischen Amsterdam und Rotterdam angesprochen, meint van Dongen: «In Amsterdam bewegt sich momentan ungeheuer viel, obwohl bis vor einigen Jahren Rotterdam die Speerspitze der modernen Architektur war. Lange Zeit hat man sich hier in Amsterdam von der Vorstellung leiten lassen, die Stadt so gut wie möglich zu konservieren, da Kohärenz, Schönheit und Gemütlichkeit über alles gestellt wurden.

Anders in Rotterdam, wo man nach dem Krieg bestrebt war, eine gänzlich neue Stadt aufzubauen. Man wollte eine Stadt, die sich von der traditionellen holländischen Bauästhetik unterscheidet und gegenüber Experimenten aufgeschlossen ist.» Frits van Dongen gibt aber zu bedenken, dass Rotterdam in den letzten Jahren mächtig aufgeholt hat. Immerhin gebe es hier Rem Koolhaas' Office for Metropolitan Architecture, die legendäre Talentschmiede für junge Architekten, aus der etliche internationale Stars hervorgegangen sind. Und man solle nicht vergessen, dass Koolhaas auf der Wilhelminapier, direkt hinter Ben van Berkels grandioser Erasmusbrükke, den spektakulären MAB-Tower, ein hybrides Gebilde aus geschichteten Volumina, bauen wird.

Aber van Dongen erinnert sogleich daran, dass Amsterdam mittlerweile ganz neue Massstäbe gesetzt hat: «Neben den neuen Zentren in der Hafengegend sind wir damit beschäftigt, auf dem künstlichen Archipel Ijburg eine neue Stadt entstehen zu lassen. Das Ijburg-Projekt ist typisch holländisch. Es wird 50 000 bis 60 000 Menschen neuen Wohnraum verschaffen.»

Rem Koolhaas und seine Talentschmiede